Story Behind the Story

I wrote Words in the Dust by accident.

At the beginning of 2004, my six years of part-time service in the Iowa Army National Guard were almost over. I planned to teach high school English and write books about kids living the adventure of growing up in the small towns of Iowa, like I had. But just like Zulaikha, I found out that life doesn’t always go according to plan. In January, the Army called me to active duty, and in late June of 2004, I left America for the first time in my life and found myself transformed from aspiring writer to terrified soldier, in the middle of war-torn Afghanistan.

Based on what I knew about the war from television and from my Army training, I had expected my unit’s mission to focus on hunting down terrorists—shooting and being shot at by the same kind of monsters who killed so many Americans on 9/11. Instead, as I sweated in a tent at the air base in Bagram, Afghanistan, I was shocked to hear that my unit would provide security for the reconstruction of the country, which had been devastated by many long years of war. Specifically, we were going to be assigned to one of the Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) stationed at small bases around Afghanistan. These PRTs were designed to help the Afghan people establish schools and improve roads and communications. The Army hoped the peace secured by the PRTs could offer Afghans a chance to build a better future for themselves, free of the influence of the oppressive Taliban militias.

To my everlasting shame, I was upset when I heard about my peacekeeping assignment. I remembered the horrible images I’d seen on 9/11, and I blamed the Afghans. I made the terrible mistake of assuming that most of the Afghan people were just like the terrorists. I felt that if I had to be taken away from my home and family, I wanted my chance to make the terrorists pay.

When I reached my station in the western Afghan city of Farah, though, my feelings began to change. Instead of finding American-hating monsters, I met kind people and a lot of smiling, curious children. Afghans offered friendly greetings when we came to their villages. Some of them invited us to dine with them in their homes. A few times, they even helped us dig our Humvees out of the mud when we were stuck. I began to understand the difference between dangerous groups like the Taliban and the normal, peace-loving Afghan people.

After about a month, our first load of mail finally arrived. A package from my wife contained a paperback copy of a classic children’s book by Katherine Paterson called Bridge to Terabithia. In a difficult time, when food rations were low and I was feeling very scared and lonely, I read this wonderful story of true friendship. It reminded me of hope and peace and beauty. That same day, I stood at my guard post, looking over the top of the wall that surrounded our tiny compound. Across the street, I saw a little Afghan girl in a dirty dress with no shoes. She dragged a small cardboard box with a piece of string. It was maybe her only toy. As I looked at her and remembered all the Afghan children I had seen, I thought about how much they were like the kids in Bridge to Terabithia. They seemed to be full of imagination. They wanted to have fun and friends. A chance to grow up safe.

Finally, I had to admit that all along, I had been wrong about the Afghans. That poor little girl had nothing to do with 9/11. She was not the enemy. She was as much a victim of the Taliban and Al Qaeda as I was. She was more of a victim. At that moment I took my peacekeeping and reconstruction mission to heart. I began to be as respectful and helpful as I could to the Afghans I encountered. I even volunteered for extra missions that would allow me more interaction with the people, especially if it meant a chance to help the children in some way.

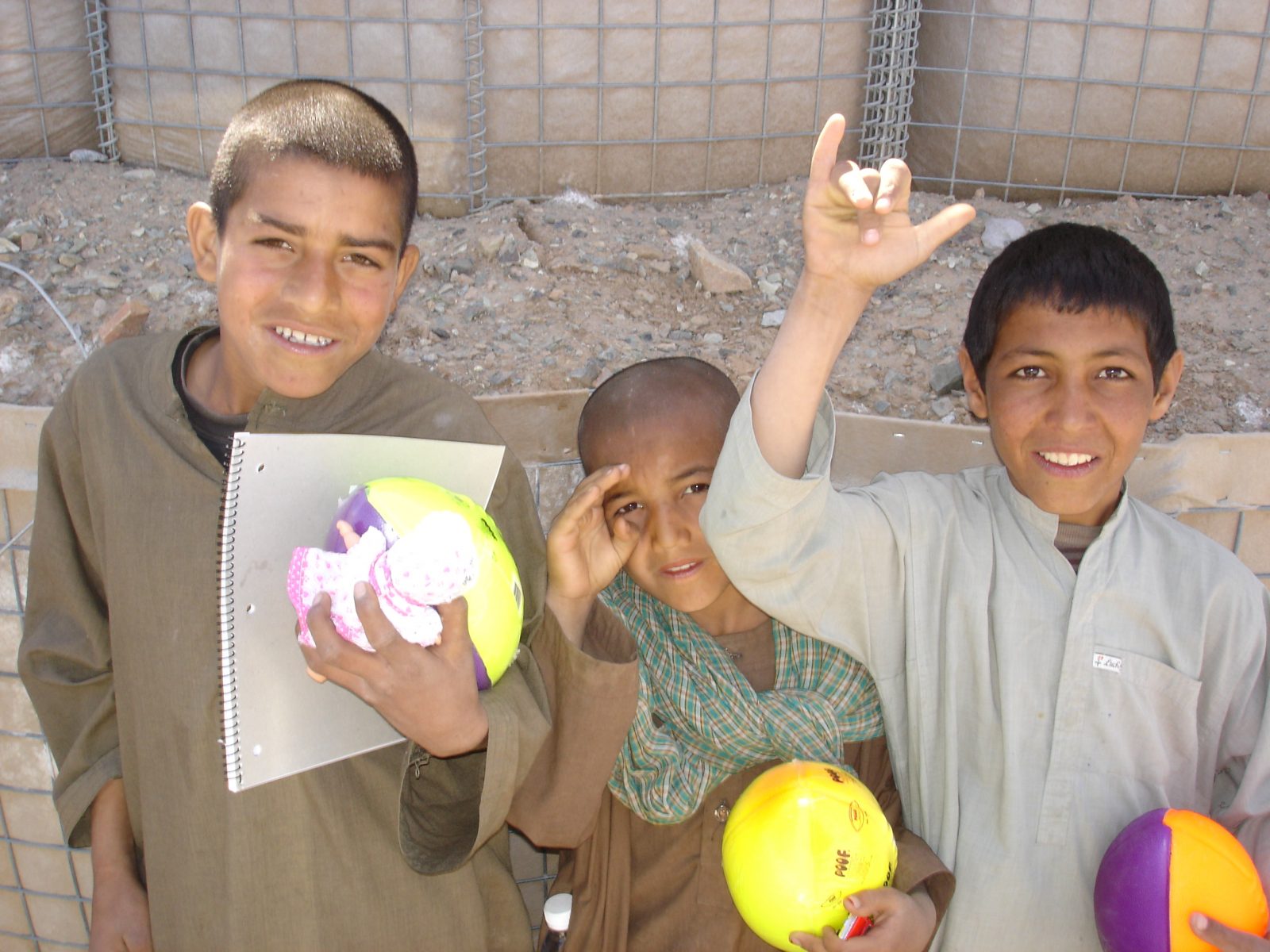

My unit spent our year on duty helping to build schools, providing security for the presidential elections, and handing out toys and candy to Afghan boys and girls. We worked hard to show the Afghans with whom we lived and worked that we were trying to help. We weren’t perfect, and I am very, very sorry that we did not help even more than we did, but partly because of our efforts, Farah and western Afghanistan were relatively peaceful in 2004 and early 2005.

As with so much else of my experience in Afghanistan, the girl who inspired the character Zulaikha came into my life by accident. My unit was on a mission to make contact with the elders of a village north of Farah. Our commanders wanted to ask the elders if there was any way the Americans could help improve the village. On this mission, one of the soldiers saw a girl with a cleft lip. That is, she was born with the two segments of her upper lip not joined in the center. In addition, her nose was disfigured, and her upper set of teeth were badly crooked, some sticking out almost straight forward. These sorts of birth defects occur in the United States too, but American doctors almost always perform corrective surgery early in the child’s life. In the case of this Afghan girl, however, surgery would have been hard to get and very expensive. Also, the Taliban who ruled Afghanistan during her early childhood and enforced harsh rules based on their strict interpretation of Islamic law forbade almost all contact between unrelated males and females and would probably not have allowed a girl to see a doctor anyway.

A short time later our chief medical officer, a woman not unlike Captain Mindy in Words in the Dust, led a second mission to the village to locate the girl and see if we could arrange corrective surgery for her. It wasn’t a mission that came down from high command, but one my fellow soldiers and I felt strongly about. After all, if we couldn’t at least try to help this girl, what good were we?

Almost miraculously, we found the girl we were looking for soon after our arrival. We tried to be friendly, but given that we rolled into town in armored Humvees, I imagine she was scared when she realized we had come looking for her. Although she was timid and for the most part kept her mouth covered, she had a quiet dignity and a spark of courage in her eyes. The girl’s name was Zulaikha. After meeting her, we knew we had to do whatever we could to get her the help she needed.

Since her surgery was not part of our assigned mission from the Army, my fellow soldiers and I pooled our money together to buy taxi fare to a nearby airport for Zulaikha and her uncle as well as civilian plane tickets to transport them to our air base at Bagram. An Army doctor there volunteered to conduct the surgery. When she returned to our outpost in Farah, I was amazed at how much she had changed. Not only were her lip, teeth, and nose completely different, but her demeanor had improved as well. She was still quiet and shy, as anyone might be around strangers, but she no longer covered her mouth with her shawl or her hand. Better yet, she smiled. The last time I saw her, she was riding in the back of one of our trucks, on the way home through our compound’s front gate. Had I not been sent to Afghanistan, I would never have known about her. I thought about all the people back home who might never know about her. Her birth defect was only one of the many obstacles that she would have had to endure in her young life, but she faced it with remarkable strength. To me, she represented all Afghan girls who are struggling to make better lives for themselves and for their families, and even though she lacked the ability and resources to tell the world her story, that does not mean that it does not deserve to be told. She looked back at me as she rode away and although she could not hear me or understand my words, I promised her I would tell her story. The result is Words in the Dust, a fictional account inspired by the incredible people I was blessed to meet in Afghanistan.