Story Behind the Story

In the course of any given day, I dream up dozens of quick stories. Think about it. Have you ever been sitting in a quiet classroom and wondered, “What would happen if I just screamed out loud right now?” Have you ever watched a bird in the sky overhead and imagined what it would be like if you could fly? From those kinds of questions come the beginnings of stories. The trouble is, most of those thoughts can’t support a full novel. So most of the time, when I have an idea for a novel, I don’t write it down. If it is an idea that might really become a book, the idea will be stuck in my head, growing, expanding, until finally it has enough detail that I can get started working. That is the normal way I start writing novels.

Divided We Fall did not happen this way. At all. Whereas I grew up in Iowa, for the last several years, I’ve lived in Spokane, Washington, very close to the border with northern Idaho. I was driving to church on Easter morning, when an idea came to my head that I could not let go. What if a kid was in the National Guard assigned to pull guard duty on the state line? I imagined tanks and armored personnel carriers lined up on both sides of the Idaho/Washington line, closing off I-90. But that’s not a novel. I began to wonder, why is the standoff happening? How did the teenage guy get involved in it all? These questions and others continued to fly through my head through the church service, despite my strongest efforts to ignore them and to pay attention.

When I returned home that day, even though there was a brand new episode of Doctor Who waiting for me on the computer, I did something I never do on the first day of thinking up a new story idea. I started to write. On that day, I came up with Divided We Fall’s prologue, the bit at the start of the book that begins: “I am Private First Class Daniel Christopher Wright. I am seventeen years old, and I fired the shot that ended the United States of America.” I have so rarely been so excited about writing! That day, I wrote the rest of the prologue and the first couple of paragraphs of the first chapter. Normally I change the beginnings of my books many times through the revision process, but the beginning of the published Divided We Fall is nearly exactly what I wrote that first day.

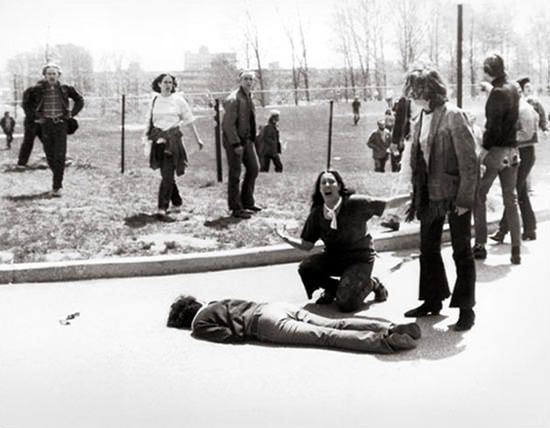

Since high school, I have been horrified and fascinated by the Kent State University massacre of May 4, 1970, where Ohio National Guardsman shot and killed four unarmed young people and wounded nine others on the Kent State campus. That incident has remained with me for years, and it is the inspiration for the Battle of Boise National Guard shootings that spark the standoff in Divided We Fall.

After I decided that the standoff on the state line would be caused when Idaho Governor Montaine orders the National Guard and state police to prevent United States federal law enforcement from entering Idaho, I discovered Article 14, Section 6 of the Idaho State Constitution which reads: “No armed police force, or detective agency, or armed body of men, shall ever be brought into this state for the suppression of domestic violence, except upon the application of the legislature, or the executive, when the legislature can not be convened.” I couldn’t believe the perfect law I needed was right there in Idaho’s constitution. I would build the book around what would happen if the Idaho governor used that section as justification for keeping federal law enforcement and troops out by force.

This conflict between the Idaho National Guard and the United States military echoes at least one real historical event. In 1957, nine African American students were enrolled to begin the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School. Orval Faubus, the governor of Arkansas, ordered the Arkansas National Guard to physically prevent the racial integration of the school. In response, President Eisenhower sent federal soldiers to Little Rock. He also federalized the entire Arkansas National Guard, placing them under his own command and ordering them to stand down. In Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957, the soldiers of the National Guard obeyed the president’s orders. But what if they hadn’t? What if they had continued to obey their governor and refused to allow the school to be integrated? Would President Eisenhower have given the order for federal soldiers to fire on the National Guardsmen? Would he have ordered people to be wounded or killed in order to enforce the order for racial desegregation? In Divided We Fall President Rodriguez orders the entire Idaho National Guard to report for federal duty. Governor Montaine asks the Idaho Guard to remain under his command, placing Daniel Wright and other Idaho Guard soldiers in a complicated situation, but it’s a situation that has happened before and might happen again.

Idaho’s nullification of the Federal Identification Card Act mirrors an attempt by the Idaho House of Representatives to nullify the Real ID Act during the George W. Bush administration.

I’ve watched and listened carefully to the news and to commentary media to imitate the way it reacts to major national and world events.

There are many other elements of Divided We Fall that are inspired by real life events, but I don’t want to spoil the story too much. I leave it to readers to find such things.

Writing Divided We Fall was a lot of fun, and I hope readers enjoy it.